"SHWANS!"

"What does a person do when he writes about art? Point one, he can describe what he sees. But since that feels somewhat simplistic and dishonourable, - after all, he's some kind of artist too, isn't he? - he can, point two, describe what he jolly well sees and the other doesn't. This can sometimes - artists are always getting in each others' way - take on pedantic traits or aspects of a conspiracy so that, in the last instance, point three, it turns into a description of what the other should see. Only if someone has had the misfortune of studying history of Art and has become convinced that only if you get a how-to-look-at-Art certificate, you are able to describe, point four and terminus, what another could have seen - if he had studied history of Art, of course."

G. Komrij

The printed out drawing featured here, comes out of the exhibition's guestbook. Hundreds of visitors were given the opportunity to write out their criticism of "Zie tekening" (cfr. drawing) in the book. The attraction of such a book for would-be critics is its anonymous aspect. You can write and draw whatever comes to mind, and in a public place at that, and still get away with it.

There is therefore something moving about the drawing and it is probably the odd combination of text/image that does it.

The composition is perfect: a small drawing, more or less in the middle of the page but not exactly in the middle. Actually just slightly above which makes it all the more thrilling. An overwhelming feeling of peace emanates from this depiction, and because of all that white, your glance is irresistibly attracted by what has been drawn. It's a rudimentary rendering of a man's genitals. You can't call such a drawing original, you see them everywhere in public toilets and on freshly painted façades of bourgeois houses.

We could label it as being a most ordinary burst of juvenile behaviour, had the puzzling Shwans not been added to it.

Is a certain Shwans the author of this piece? (Günther Shwans aus Saarbrücken!?)

Is Shwans an unusual addition to the all too well-known list of penis, cock, prick, dick, willie, John Thomas and hard-on?

Or is it a terse comment about the exhibition? ('How did you enjoy it, Günther?'- 'Shwans!!')

Whatever, there was someone in Lier who wanted to pour out his heart and we will assume that the person in question did not find the exhibition to his liking and expressed his negative feelings with the Shwans drawing that would become part of the catalogue a few months later.

This has more logic to it than would appear at first sight. The drawing could have been part of "Zie tekening". By showing functional and autonomous drawings arbitrarily, thus not based on some sort of hierarchy or canon, an open exhibition came into being that seemed boundlessly extensible. Moreover, the choice of the organisers to avoid a layout in categories, invited the visitors to browse around hypertextually. (A Hypertext is the opposite of a classic, linear text - you follow a trajectory that has been pre-written by the author - a network of interlinked text units in which the reader selects a trajectory that fits in with his own preferences and interests).

The drawings function as 'text units'. Spectators were able to find their own way around.

One could also assume that drawings can be 'read' as hypertexts, because of the very nature of the medium itself.

According to Marshall McLuhan, author of the cult book 'The medium is the message', there are two fundamentally different types of media that he calls 'hot' and 'cool'. The hot medium is a medium that overflows the sense that it addresses. A cool medium on the contrary, offers little information to the sense it plays on: each grain of the photographic emulsion is touched by light and is thereby informed. A drawing is a cool visual medium because it always contains empty parts that the artist hasn't touched with a pencil or a brush. To draw a bull, one single line suffices, whereas to take the picture of a bull, every single dot in the surface gets filled in. The drawing of a bull forces the spectator to imagine something to complete the image at the sight of the single visible line. A cool medium stimulates the viewer's fantasy.

The minimalism, the sparsity that is so typical of drawing incites the spectator to reconstruct the drawing. In doing so, he collides with the maker of the drawing, because drawings are, essentially speaking, the materialisation of thoughts and movements of the drawer's mind and are therefore never really finished 'off'.

The mentioned sparsity is somehow tempered by the support. As a matter of fact, it can be just about anything; all sorts of paper, cardboard, wood (the cabinet maker and his pencil), sand (artist Markus Raetz and children of all times), a rock wall (Altamira), a road (the police and a piece of chalk), a wall (artist Sol Lewitt and all those children again), and so on.

The interaction drawer-drawing instrument-support is a constant during the act of drawing and occurs at both sensory and mental levels. The ultimate result is an image in which the support and the drawing seamlessly intertwine and reinforce each other.

The material used for drawing has not changed all that much throughout the centuries.

This explains that drawings from various periods in time tone in with each other - "Zie tekening" was a perfect example of this.

This 'all us drawings together' brotherhood that hits the eye is not achieved merely by the use of material. In the Western culture, and finally till late in the twentieth century, drawing was somehow subordinated to painting and sculpture. This takes on a more pejorative tone than it should, because it is precisely thanks to this serving and modest role that the drawings from various periods in time can hang side by side in perfect harmony. Drawing is in fact the best medium by far to study and depict what we have observed. What you haven’t drawn, you haven't seen.

Since drawings and studies always form such a close tandem, drawings are able to preserve their utterly intimate nature. Up till the 19th century, they seldom left the artist's workshop because in those days, art was synonymous with paintings and sculptures. Orders from the ecclesiastical and secular leaders resulted logically in restricting the artist's freedom of movement: the period's style and orders were most compelling. Paradoxically, drawing escaped those demands thanks to its modest and studious character. This is apparently also the reason why drawings that are a few hundreds of years old look so 'fresh' and still move us today in a very direct manner. As spectator, no need to mention those so very annoying 'style categories' (Michelangelo: Renaissance!- Rembrandt: Baroque!). You are directly in contact with the maker of the drawing. With his thoughts, to be precise.

It is only in the middle of the 19th century that the artist, and specifically with the invention of photography and society becoming more middle-class, slowly frees himself from the straitjacket of orders: photography 'imitates' reality far better that paintings. Art becomes autonomous, the artist has one person to answer to, and that is himself.

Even in our highly technological civilisation, drawing is still standing. In Art Academies and plastic Arts, it is slowly but surely considered as a mode of expression in its own right. And how it keeps up within a wider social context has become surprisingly obvious with the functional drawings shown here in Lier.

Besides, they have demonstrated that 'autonomous' and 'functional' are drifting concepts, because they are interchangeable in more than one instance.

In the Renaissance, a period in which science and art were closely linked, Leonardo Da Vinci drew beautiful draft projects for armaments from a purely functional viewpoint. And that is how they were considered in his day. Throughout the centuries, they acquired an autonomous statute.

"Zie tekening" has made it very clear how relative the distinction is when one casts an unbiased glance at drawings, whether or not the makers meant them to be functional or autonomous. In the end, one is always confronted with - and this remains so fascinating in drawings - that unique characteristic of man: thought.

And thought is probably something that our Shwans-drawer always sets on low.

Wouter Coolens - September 2004

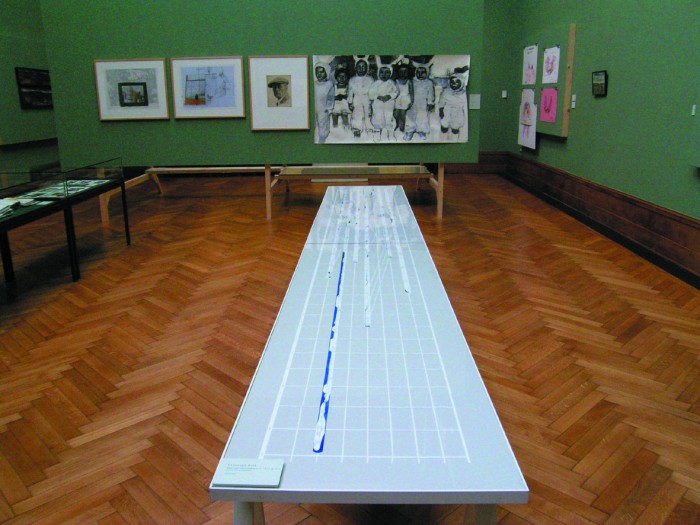

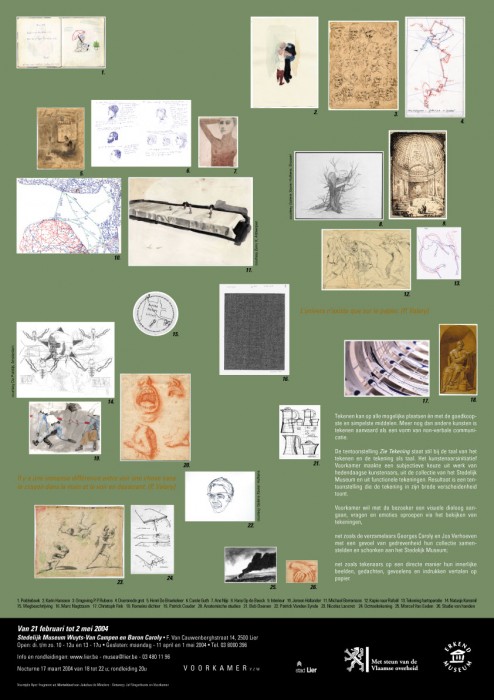

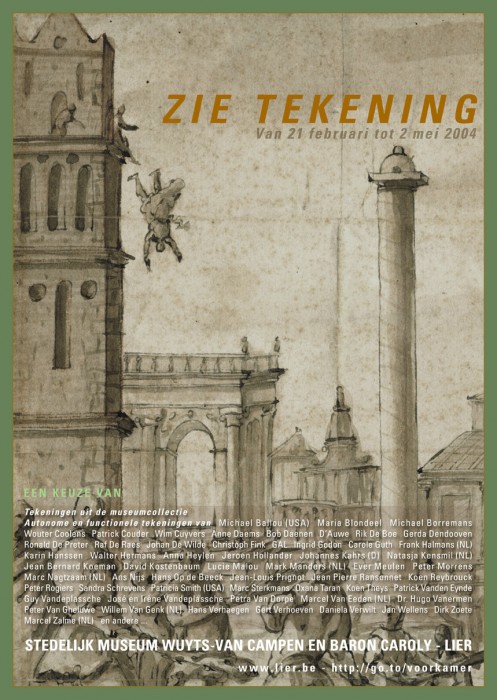

Zie tekening, Museum Wuyts-Van Campen & Baron Caroly Lier

Autonomous and functional drawings of:

Michael Ballou (USA), Maria Blondeel, Michael Borremans, Wouter Coolens, Patrick Couder, Wim Cuyvers, Anne Daems, Bob Daenen, D’auwe, Rik De Boe, Gerda Dendooven, Ronald De Preter, Raf De Raes, Johan De Wilde, Christoph Fink, GAL, Ingrid Godon, Carole Guth, Frank Halmans (NL), Karin Hansen, Walter Hermans, Anna Heylen, Jeroen Hollander, Johannes Kahrs (D), Natasja Kensmil (NL), Jean Bernard Koeman, David Kostenbaum, Lucie Malou, Mark Manders (NL), Ever Meulen, Peter Morrens, Marc Nagtzaam (NL), Ans Nijs, Hans Op De Beeck, Jean-Louis Prignot, Jean Pierre Ransonnet, Koen Reybroeck, Peter Rogiers, Sandra Schrevens, Patricia Smith (USA), Marc Sterkmans, Oxana Taran, Koen Theys, Patrick Vanden Eynde, Guy Vandeplassche, José en Irène Vandeplassche, Petra Van Dorpe, Marcel Van Eeden (NL), Dr. Hugo Vanermen, Peter Van Gheluwe, Willem Van Genk (NL), Hans Verhaegen, Gert Verhoeven, Daniela Verwilt, Jan Wellens, Dirk Zoete, Marcel Zalme (NL),...

Drawings from the collection of the museum:

Henri De Braekeleer, Raymond de la Haye, Gerard De Lairesse, Hendrik Johannes Haverman, 16th and 17th century Italian School, Nicolas Lancret, Willem Linnig, F.J. Navez, Ignace Raeth, Félicien Rops, Andreas Schelfhout, Han Van Meegeren, Theo Van Rysselberghe, Theo Verstreken, 16th and 17th century Flemish School,...